Volume 1, Issue 4-5 / March-April 2009

This opinion piece highlights the plight of refugees who live without permission in urban areas, and asks why the Kenyan Government and UNHCR do not adopt policies that reflect this reality.

I have observed many refugees from urban areas coming to Kakuma Refugee Camp for the recent headcount, causing an unexpected increase in the camp population. This is a clear indication that thousands of refugees who are counted as “residents” in Kakuma Camp are actually residing in urban areas without permission. In observing this situation, I ask whether it is fair to continue pushing urban refugees into “illegal” residence in urban areas. Why don’t UNHCR and the Kenyan Government adjust policies to respond to this reality?

In Kenya, refugee residency can be separated into two major categories: urban and camp refugees. Under Kenyan policy, refugees are expected to stay in designated refugee camps—these are “camp refugees.”

Urban refugees form the other major category of refugee residents, and they fall into one of four sub-groups. The first is recognized refugees who are fully accommodated and assisted by UNHCR, with special permission to live in urban areas (chiefly Nairobi). UNHCR authorizes urban residence only in rare cases. The second is recognized refugees who have a legal permit to live in urban areas but do not receive assistance from UNHCR. Their permit is renewed by UNHCR at the time of expiry. The third is illegal refugees who are not recognized by UNHCR or the Kenyan Government. These persons live and work in Nairobi illegally as undocumented immigrants.

The last sub-category of urban refugees—and this is the category that has attracted my attention—includes recognized refugees living in urban areas without permission. These refugees are recognized by UNHCR, but they are mandated under Kenyan policy to stay in the refugee camp. For their own reasons, they prefer to stay in an urban area and to cover all their expenses independently without assistance from UNHCR. They visit the camp only when called by UNHCR, especially for head counts, then return to their urban residence.

Unauthorized urban refugees are either supported by family or engage in some form of employment. It should not be forgotten that this economic exchange has a major impact on the development of urban economies. On top of self-reliance, it is also important to consider refugees’ concerns. Some of them feel unsafe in the refugee camp, and services in the camp are very limited. People must look elsewhere for better education and communication media in order to realize career opportunities.

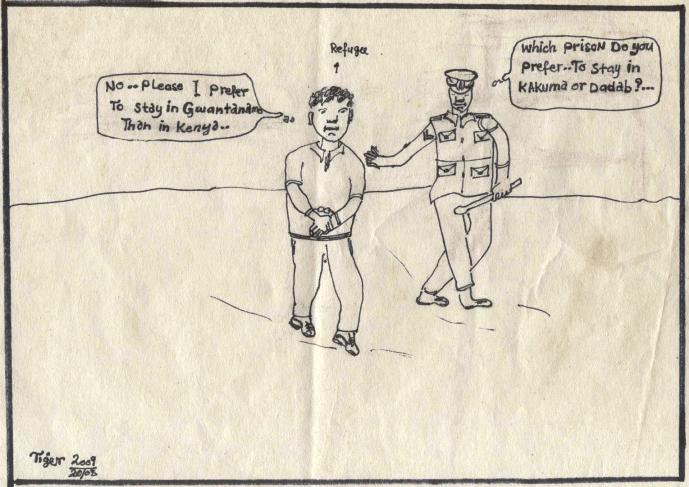

But living as an unauthorized urban refugee carries heavy risks. Under the Kenyan Refugees Act 2006, it is an offense to live without permission outside of designated camps. Due to this, refugees cannot obtain permits to work in the formal sector or run recognized businesses. This also opens the way for harassment by police, as well as real legal risks of heavy fines or jail. These refugees live in a state of perpetual insecurity in the absence of legal protection.

Here is the reality: most refugees stay in the camp for years. But refugees need to see new changes to their life. Long stays in the camp with no help from UNHCR create a lack of confidence. I believe refugees should develop their confidence in life to become independent. This includes working in the private sector and opening small scale businesses as a means of self-reliance.

I argue that the authorities should respect refugees’ interests and protect them from the risks of staying in urban areas illegally. It is also necessary to save their resources from unplanned spending during their travel between urban areas and the camp again and again.

In light of this, I suggest the following: Why don’t UNHCR and the Kenyan Government think of these groups and provide them with legal permits to live in urban areas, while continuing to respect their need for a durable solution?

One must consider that Kakuma Refugee Camp is 1,000 km from Nairobi, where the majority of urban refugees live. My suggested proposal may have positive effects in contributing to economic development of urban areas; saving time and money of frequent travel; and also in minimizing the risk of road accidents which occur during refugees’ repeated travels between the camp and cities.