Volume 1, Issue 4-5 / March-April 2009

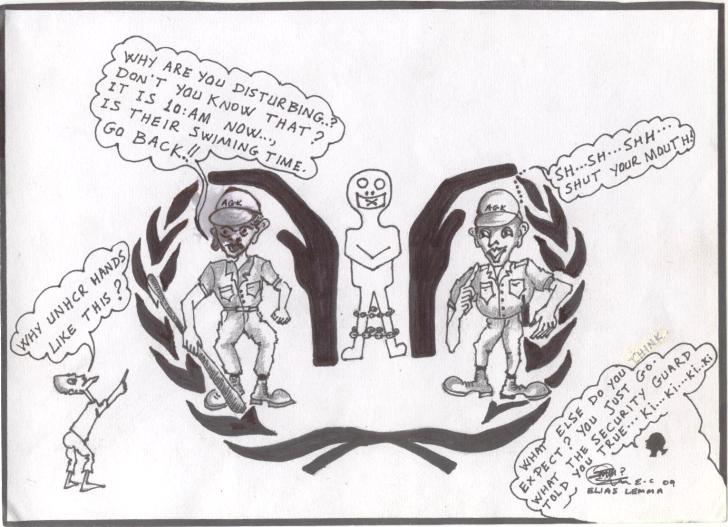

Asylum seekers feel that basic standards of procedural fairness are not being upheld in the RSD process in Kakuma, and fear the consequences of rejections.

What happens to asylum seekers who live in Kakuma Refugee Camp for years and are rejected as refugees by UNHCR? Some flee to other countries; some disappear into the urban fringes. And some remain in Kakuma without food or services. They are waiting, they say, for UNHCR to change their stance on RSD rejection—but that hope is minimal.

What happens to asylum seekers who live in Kakuma Refugee Camp for years and are rejected as refugees by UNHCR? Some flee to other countries; some disappear into the urban fringes. And some remain in Kakuma without food or services. They are waiting, they say, for UNHCR to change their stance on RSD rejection—but that hope is minimal.

KANERE conducted in-depth interviews with ten rejected asylum seekers currently living in Kakuma, and followed up on ten others who have migrated elsewhere. They share similar stories of rejections based on unclear evidence, and a feeling that basic standards of procedural fairness are not being upheld by UNHCR eligibility lawyers in Kakuma.

A rare second chance

Tilahun* is an Ethiopian refugee who was initially rejected by the UNHCR Eligibility Office in Kakuma. He arrived in the camp in 2005 after being persecuted in Ethiopia, where he was intimidated and tortured while imprisoned at a military camp in southern Ethiopia.

While in prison, he was visited by the delegates of the Red Cross of Addis Ababa. “That saved my life.” Tilahun was eventually able to escape prison and reach Kakuma Refugee Camp, where he encountered unexpected difficulties.

Despite being able to provide documentation from the ICRC verifying his visitation at Moyale Police Station, Ethiopia, Tilahun was rejected by UNHCR. The reason for rejection stated on his letter was credibility.

“I believe the problem must lie in that Eligibility Office and not in my case,” says Tilahun. “I escaped death in Ethiopia, I had documentation, yet no reason was given to me for my rejection.” (Following procedure, UNHCR did not provide specific reasons for why his testimony was judged not credible.)

After his rejection, Tilahun became depressed. He says that he does not have freedom in his “sense of living,” and feels that his life holds no meaning. “Survival is not easy in the camp. I don’t see why I’m alive and just keep on talking to myself.”

Finally, Tilahun’s case came to the attention of local Kenyan Government officials, and he was able to appeal to the Camp Manager. “I got my ration card through the assistance of the Camp Manager. Currently I’m getting food rations and I’ve also undergone UNHCR head count.”

Tilahun was fortunate to be assisted with a ration card after receiving a final rejection from UNHCR—many rejected asylum seekers are never given another opportunity to seek humanitarian assistance on Kenyan soil. But he still does not have recognition as a refugee: “Unfortunately, the Camp manager only recommended my case but he does not do RSD,” explains Tilahun.

The UNHCR rejections deeply affected Tilahun. “My eligibility interview was not fair, equal, or just! I was denied food, shelter, and protection between 2007 and late 2008. My life was totally sad and I was depressed.”

Living unrecognized

With the receipt of a final rejection letter from UNHCR, individuals are suddenly relegated to the most uncertain margins of society. Denied asylum in Kenya, they join the class of illegal migrants in Kenya; but afraid to go home, they often linger.

In the rejection letter, asylum seekers are informed to leave the camp within 30 days, after which time his or her ration card will be deactivated. “You are therefore not a person of concern to UNHCR. As a result, we have closed your file and we are unable to assist you,” states the rejection letter.

Some rejected asylum seekers take off for another country in hopes of gaining asylum elsewhere. KANERE followed up on the cases of four asylum seekers who made their way to Southern Sudan in search of a better standard of living. They say they make frequent visits to the camp to check whether UNHCR and the Kenyan Government have changed their stand on RSD rejections.

Two individuals are reported to have gone to Uganda, but KANERE could not reach them for comment. Another group of five rejected asylum seekers went to Nairobi, where they say they face many difficulties of insecurity and financial instability.

Living without UNHCR recognition carries many risks for rejected asylum seekers in Kenya. Many become isolated and do not freely interact with refugee communities. KANERE spoke to ten rejected asylum seekers remaining in Kakuma Camp.

After an RSD rejection, asylum seekers are often confused and fearful about their life in Kenya. If they decide to remain in Kakuma, they face a difficult situation. Some Ethiopian refugees are educated and can afford to work with NGOs. But others are not educated, and after their ration cards are deactivated following a UNHCR rejection, they suffer economically and psychologically.

Rejected asylum seekers shared their grievances with KANERE: they don’t hold an identity, they are denied food, and there is no body responsible for protecting their human rights in the camp or Kenya.

The RSD process and establishing “credibility”

During the RSD interview, the Eligibility officer makes a detailed transcript of the interviewee’s responses, behavior, and demeanor during the meeting. A typical eligibility interview takes about two hours, sometimes more. Applicants may choose to use an interpreter, and the UNHCR office in Kakuma employs recognized refugees as interpreters for this purpose.

Before an interview, UNHCR Guidelines require that asylum seekers be informed about the purpose and scope of the RSD procedure, and the right to take a break. They should be informed of the obligation to be truthful and to make the most complete disclosure possible about their refugee claim.

Asylum seekers may also be accompanied by a legal representative during the RSD interview, but this rarely happens in Kakuma due to the absence of legal aid resources.

After completing the interview, UNHCR Guidelines require that the eligibility officer read back elements of the RSD interview transcript that are most relevant to the determination of the claim. Any part of the interview that seemed unclear, or where interpretation difficulties may have arisen, should also be read back. “Unless the applicant has had the opportunity to explain inconsistencies or evidence that is otherwise not believable, the Eligibility Officer may not make a negative credibility finding in the RSD assessment on facts that are material to the refugee claim” (4-10).

As a general rule, RSD decisions should be issued within one month after the interview, and should not take more than two months. Procedures for reporting mistreatment or misconduct should be disseminated to asylum seekers. UNHCR offices are required to set up procedures for comment and complaint regarding the services of interpreters, which should include follow up on complaints received.

The majority of rejected cases at UNHCR Sub-Office Kakuma are dismissed not because the asylum claim fails to meet the legal criteria for refugee status, but on grounds of “credibility.”

As one UNHCR Protection Unit official puts it, “A final decision for granting a person with refugee status comes after that person has given genuine information, accurate and well-founded reasons why he left his country and can’t return there. So one must prove this clearly and give evidence with true accounts, which most refugees are not able to prove and therefore cannot be accepted as refugees.”

KANERE attempted to reach the UNHCR Protection Officer to request statistics on the acceptance rate of asylum requests in Kakuma, but was unable to obtain information.

After a first-instance rejection, there is no channel for appeal through an independent body. Instead, asylum seekers must appeal to the same UNHCR office which rejected them previously. The reasons for rejection are not stated in either the first or second instance rejections from UNHCR. There is no independent body to monitor the RSD process of UNHCR, and rejected asylum seekers in Kakuma have limited recourse to legal aid or assistance.

Is procedural fairness upheld?

The rejected asylum seekers interviewed by KANERE claim that they were not treated fairly according to UNHCR procedural standards during the process.

Despite UNHCR Guidelines, asylum seekers report that they are rarely read back portions of their transcript following an interview with Eligibility Officers in Kakuma. Tilahun says that his case was never read back to him after the conclusion of the interview, and neither was he shown the written transcript of the interview.

Asylum seekers say they are not informed of their rights or obligations during the interview before the RSD interview process. Many of them went into the interview clueless about what it would entail. A few of the asylum seekers who spoke to KANERE did not even know the legal definition of a refugee.

“I know a few things about my rights but I was not informed about my right during my RSD interview, and I was not informed on the legal representative or refugee definition,” says Mohamed,* an Ethiopian asylum-seeker rejected by UNHCR in 2007. If he had been equipped with knowledge of his rights, he says, “I believe I would have won this fight before.”

A majority of interviewees state that they had complaints over eligibility officers and their interpreters, yet their complaints were never heard or addressed. Due to this inability to clarify mistakes they felt had occurred during interviews, many feel that they were rejected based on an inaccurate case file.

“During my second RSD interview, I raised many clarifications and corrections to be done on my case file; like my place of birth was Nagele and not Walega as listed. But there was no changes done on my case concerning those mistakes and I was rejected,” states Mohamed.

Another rejected asylum seeker, Abera,* arrived in October 2003 and was rejected by UNHCR in December 2006. “My case was conducted in a very bad manner that led to rejection. There were problems of miscommunication and I had quarrels with the interpreter in front of the eligibility lawyer,” he says. At one point, the quarrel escalated to the point that the interpreter stood up and declared, “If you are uncooperative we can’t help you.” He says that the interpreter and Eligibility Officer told him that they do not have a lot of time and he should hurry up. “I felt that was not justice and who am I to make any complaints yet to whom?” he asked.

“I believe the interpreter did mistakes on my file. The eligibility lawyer was frequently making harsh orders,” says an Ethiopian woman who was twice rejected by UNHCR. During her interview, she observed that her interpreter was acting in a very strange manner, frequently interrupting her interview process. “He behaved like a mad person. Currently that interpreter has gone crazy and is a mad man in the Ethiopian community,” she says.

She was concerned that her case had not been recorded accurately and shared this concern with the Eligibility Officer at the end of her interview. But she never had an opportunity to correct the misinformation. “I was told the office will contact me to finalize my case, yet I was never consulted until my final rejections,” she says.

Many of the rejected asylum seekers say they want a chance to review their files and submit their complaints for review.

Atnefu* says that he felt powerless and uninformed throughout the entire RSD process. “It was just ruled and decided. Why was I just ordered to sign the RSD form immediately before the interview and afterwards—is this a fair decision?” he asks.

Interpreters and miscommunication

In their accounts of the RSD process, asylum seekers face communication difficulties in articulating their claims which often resulted in negative RSD decisions. From the perspective of the rejected asylum seekers interviewed by KANERE, interpreters are not trained adequately to serve the delicate task of detailed translations in a legal case.

“I had a great deal of problems with interpreters who misinterpreted my story. The two interpreters I came along didn’t even look trained and don’t have good English skills,” says Mamush,* a rejected asylum seeker.

Atnefu* fled Ethiopia after he was persecuted by the EPRDF (Ethiopian Democratic Party) security forces at Mega in Southern Ethiopia. He was detained at 147 Military Camp at Boru Luboma, where he served as a leader of the camp prisoners for two years. “After two years and some months I managed to escape from the military camp together with many other prisoners at night, and I managed to cross the border into Kenya in 2004,” he recounts.

Atnefu states that he was not informed that he would be using an interpreter, who spoke to him in an unfamiliar dialect. Before the interview, he was asked to sign a form, but the contents of that form were not explained to him. He was again asked to sign another form after the interview without an explanation.

He was finally rejected by UNHCR in 2007. Now, Atnefu splits his time between Kakuma Three and Reception Centre, living in limbo.

Zeitun* is an Ethiopian asylum seeker rejected in 2007 by UNHCR. She left Ethiopia after her husband was arrested in connection with rebel fighting that killed many people at Tuqa Division of Moyale District in Ethiopia. After he was arrested, she felt targeted and fled the country.

Zeitun believes her interpreter did not interpret her case well, but she does not know how to read or write English so she felt powerless to address the problem. “I was denied food, medical, and protection for my life together with my husband. Is this a fair work of UNHCR?” She adds that she disagrees with UNHCR’s RSD policy. She is now living alone in Kakuma Three.

Another asylum seeker, Yenh,* also claimed that he was uncomfortable with his interpreter who was speaking a different dialect. Tilahun also believes that his case was wrongly rejected due to miscommunications through the interpreter in both the first and second RSD interviews.

No response from UNHCR

KANERE attempted to reach the UNHCR Protection Officer but was blocked at the main entrance to the UNHCR Compound on three separate occasions. On the third visit, the journalist reached the Protection Officer via phone and was informed to wait until he was called for a meeting. He was never contacted.

KANERE also attempted to reach the Camp Manager but the officer was not on duty between March 10th and 12th 2009, when the journalist attempted to reach him.

Conclusion

Rejected asylum seekers ask who will be responsible to re-consider their cases after UNHCR rejects them. They feel that the RSD process is undemocratic. “What could be the stand of the Kenyan Government on our case files after staying in Kakuma Camp for over four years?” asked one Ethiopian asylum seeker.

Given the life-changing consequences of the RSD process, refugees believe there should be a better mechanism to submit complaints and appeals during RSD for review by an independent body.

After experiencing unfair treatment and sub-standard procedures of RSD by UNHCR Eligibility Officers, many rejected asylum seekers feel disillusioned. “Everyone talks about rights or human rights, but there is nothing like rights I got in Kakuma,” said Fita,* an asylum seeker who was rejected by UNHCR in 2006 and now resides in Nairobi.

“Is this a fair approach for decision-making on RSD? Are these policies coming directly from UNHCR Geneva on the asylum seekers?” asks one Ethiopian Oromo asylum seeker.

*Not their real names.