Volume 1, Issue 4-5 / March-April 2009

By Zachary Lomo

Does UNHCR have an obligation to uphold the human rights that are essential for refugees’ free and full development as human beings? Are there any circumstances where a refugee could take UNHCR to court for failing in this regard?

Zachary A. Lomo, LLB (Makerere), LLM (Harvard), directed the Refugee Law Project of the Faculty of Law, Makerere University from July 2001 to August 2006. He co-authored RLP Working Paper Series, Behind the Violence, on the causes of the war in northern Uganda, Negotiating Peace, and Whose Justice? He is currently reading for his doctorate in International Law and Refugees at the University of Cambridge.

The answers to these questions depend on one’s view about international law and its functions. My answer is yes and I will explain shortly; UNHCR has an obligation to uphold the rights and freedoms of refugees and should be sued by a refugee who has suffered harm resulting from UNHCR’s actions and omissions or plainly its decisions, policies, and practices. I reach this conclusion because I share the view of other international lawyers, such as President Rosalyn Higgins of the International Court of Justice, that international law is a ‘system of ordered conduct’ that is ‘harnessed to the achievement of common values – values that speak to us all, whether we are rich or poor, black or white, or any religion or none, or come from countries that are industrialized or developing,’[1] and I would add, whether refugee or not, international organisations in their classical sense or subsidiary organs of these international organisations or private voluntary agencies. The classical and positivist international lawyer – one who asserts that international law is a set of rules or the ‘law as it is’, i.e., law as written in the statute books or treaty or what states, following long practice and tradition, accept as law or the courts say is law – will counter this process and normative system-based perspectives as mere policy and politics and not law.

The answers to these questions depend on one’s view about international law and its functions. My answer is yes and I will explain shortly; UNHCR has an obligation to uphold the rights and freedoms of refugees and should be sued by a refugee who has suffered harm resulting from UNHCR’s actions and omissions or plainly its decisions, policies, and practices. I reach this conclusion because I share the view of other international lawyers, such as President Rosalyn Higgins of the International Court of Justice, that international law is a ‘system of ordered conduct’ that is ‘harnessed to the achievement of common values – values that speak to us all, whether we are rich or poor, black or white, or any religion or none, or come from countries that are industrialized or developing,’[1] and I would add, whether refugee or not, international organisations in their classical sense or subsidiary organs of these international organisations or private voluntary agencies. The classical and positivist international lawyer – one who asserts that international law is a set of rules or the ‘law as it is’, i.e., law as written in the statute books or treaty or what states, following long practice and tradition, accept as law or the courts say is law – will counter this process and normative system-based perspectives as mere policy and politics and not law.

From the perspective of the positivist international lawyer, the answer is likely to be ‘NO’ – UNHCR has no obligation to uphold the human rights of refugees – because there is no rule of law in any statute or treaty that explicitly states that UNHCR has a duty to uphold the rights of refugees. This school of thought of international lawyers would emphasize the rights of UNHCR to access refugees and to formulate programmes of action to provide protection to refugees and counterbalance any abuses with some statistical analysis of the overall good to refugees of UNHCR’s work. In other words, the question of upholding the rights of refugees is best addressed to states and not an international organisation such as the UNHCR. These lawyers and realists will speak, for example, about the reality and inevitability of encampment of refugees and the need to improve conditions inside them. Any other ideas will be dumped into the dustbin of ‘policy and politics’, which are not part of law.

I have problems with these mechanical and state-centred view of law, international or otherwise and will state that YES, UNHCR has an obligation to uphold the human rights of refugees whether in situations of encampment as is the case in many countries in the global south, and Africa in particular where refugees, as a matter of black letter law and policy refugees are encamped, or where refugees have chosen to live outside the refugee camps and settlements. If international law is a normative system with ‘authoritative decision-making’ for achieving common values, such as the full enjoyment of human rights by refugees as human beings, then the Charter of the United Nations, human rights law, general international law, and the Statute of the Office of the UNHCR read together provide sufficient basis for asserting that UNHCR has a legal obligation to uphold the rights of refugees and to treat them as human beings and not mere passive victims and recipients of aid, humanitarian or otherwise.

The Statute defining the powers and functions of the UNHCR provides a starting point to explaining the obligations of UNHCR to respect and uphold the rights and freedoms of refugees. Article 1 of the Statute provides, among other things, that UNHCR ‘shall assume the function of providing international protection, under the auspices of the United Nations, to refugees…’ and Article 8 of the Statute stipulates nine means by which the UNHCR will provide protection to refugees falling under its authority. The provisions of the Statute, read together with United Nations General Assembly resolutions 319 A (IV) of 3 December 1949 and 428 (V) of 14 December 1950 that established and defined the powers and activities of the UNHCR can be said to have laid down a ‘system of ordered conduct’ for the High Commissioner, aimed at the ‘achievement of common values’ – the protection of the human rights of refugees and helping states to finding solutions to the refugee problem.. These in effect give UNHCR rights as the sole subsidiary organ of the United Nations to provide protection to refugees, which is a universal common goal for all peoples of the world. The right to provide protection to refugees, however, entails the duty to uphold the rights of refugees. It is not enough for UNHCR to develop procedural standards for states parties to the 1951 Refugee Convention in order to fulfil their obligations for protecting refugees; UNHCR itself must be seen to respect and uphold the rights of refugees.

The drafting history of the Statute suggests that the drafters intended UNHCR to be the guarantor and upholder, for lack of a better word, of the human rights of refugees as defined by the Statute and later the 1951 refugee Convention and this is clearly captured in the idealism and imagery of the language of some of the members of the respective delegations that debated the draft statute both in the General Assembly of the United Nations and its Third Committee on Social issues. One member of the French delegation to the United Nations, Mr. Rochefort, while contributing to the debate on the draft statute during the 325th Meeting of the Fifth Session of the General Assembly, urging other delegates to support the establishment of the UNHCR, stated that UNHCR is the ‘new ark, which bears the hope of so many refugees throughout the world…’ The imagery of the ‘new ark’ reminded delegates of the Biblical Noah’s Ark that saved Noah’s family from the torrential rains and the ensuing floods and conveys a powerful reminder to delegates of the ‘floods’ of human rights abuses that produce refugees and that refugees face in exile and the necessity for establishing an organisation such as UNHCR to guarantee and protect the human rights and freedoms of refugees such as freedom of speech and free press, religion, association, movement, and access to education and health. Crucially, it also means that refugees have the right to participate in all the activities designed for their common good, including challenging policies that proscribe their rights and freedoms.

In the second place, as a matter of international law, UNHCR has a legal obligation to respect and uphold the rights of refugees because it possesses international personality, that is to say, it possesses rights and duties as a distinct legal person.[2] This means that it can sue and be sued although in practice, as will be explained later, it is technically, i.e., in the positivist sense, impossible for refugees to sue UNHCR in courts of law for harm or injury suffered. Another characteristic of possessing personality in international law is responsibility for injury or harm caused by the actions and omissions of an international legal person. While the Statute never explicitly stipulate that UNHCR has international legal personality, we can explain the attribution of international personality to it by reference to the authority and tasks assigned to it in the Statute and subsequent resolutions of the General Assembly of the United Nation and by analogy to the principles on attribution of international personality to an international organisation enunciated by the ICJ in the Reparation for Injuries suffered in service of the United Nation’s case, decided in 1949.[3]

In that case, the question of the international legal personality of the United Nations was addressed. The Charter of the United Nations never stipulated anywhere that the United Nations possesses international personality. The ICJ concluded that the international legal personality of the United Nations, and in effect that of any international organisation, can be deduced by ‘necessary implication’ from its competence, functions, and intention of its creators and on the basis of this the Court held that the United Nations has international legal personality of its own distinct from that of the states that brought it into existence. Borrowing from Court’s analysis, UNHCR was created by the General Assembly of the United Nations to realise a specific set of objectives – provide international protection to refugees and assist states to find solutions to the refugee problem – and it was given authority to perform tasks on the international plane. The set of activities stipulated in Article 8 of the Statute necessitate UNHCR to engage with different actors, both states and non-state actors in order to realise the overarching objectives for which it was created. Thus, Members of the General Assembly of the United Nations can be said, in the words of the Court, to have ‘clothed’ UNHCR ‘with the competence required to enable those functions to be effectively discharged.’[4] It follows that UNHCR has the right to provide international protection to refugees and the duty to respect and uphold the human rights and freedoms of refugees in the course of discharging its functions.

In the third place, international human rights law also impose an obligation on UNHCR to uphold the human rights and freedoms of refugees whether in refugee camps, settlements, or spontaneously settled. From a positivist legal perspective, no such obligation exists because international human rights instruments are treaties between states that agreed to be bound by them. For example, the 1951 Refugee Convention assigns rights and freedoms to refugees and imposes obligations on states party to it to uphold these rights. While it gives UNHCR a supervisory role, it never imposes a direct obligation, as it has done with states, on UNHCR to uphold the rights of refugees. But from a normative perspective, namely, a perspective of international law as a normative system of ordered conduct that is harnessed to achieve a common value, in this case, the upholding of the human rights and freedoms of refugees, UNHCR has a legal obligation to uphold the human rights and freedoms of refugees as human beings with dignity. From this view point, the Charter of the United Nations and the international human rights instruments are not just a set or system of rules applicable only to states but a ‘system of normative conduct’, regarded as obligatory and binding on all those vested with authority and power – whether state or international organisations – for which any departures from the norm or its violations carries a cost. Indeed, the preambular language of the Charter reflects this perspective:

“We the peoples of the United Nations

determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind, and to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal right of men and women and of nations large and small, and to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained, and to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom…”

This statement of the experiences of the peoples of United Nations and their determination to work towards a peaceful world anchored on faith in human rights, is then followed with specific purposes for the new Organisation articulated in Article 1; one of which is the ‘promotion and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all,’ of course including refugees. It follows that all actors, the United Nations, States, and other international organisations, including UNHCR, must uphold the rights and freedoms of refugees as intrinsic, inherent, inalienable to their full growth and development as human beings in all circumstances. This view of UNHCR’s obligation to uphold the human rights and freedoms of refugees differ significantly with some writers who see a limited obligation based on ‘particular circumstances of UNHCR’s exercise of its international legal personality.’[5]

Crucially, UNHCR’s obligation to uphold the human rights and freedoms of refugees is further reinforced by its control over the camps and settlements. In theory governments in many of the countries in the global south are in charge but the practice is different. In camps that I visited in Tanzania and Kenya in the autumn of 2008, and my own experiences with the refugee protection situation in Uganda, there are all the appearances of the governments of these countries being in charge but as one gets into the camp and starts to observe and interact with refugees, government, and UNHCR officials, the evidence of UNHCR operational control exercised over refugees and camps becomes apparent: it finances most of the programmes in the camps – water, health, education, security, and shelter – and all vehicles whether donated for the use of government officials or implementing partners bear not only its emblem but also unique number plates. And while one may need a clearance from government to enter the camp, UNHCR is the real gatekeeper into these closed cloisters. In some camps, it must approve permissions for refugees to leave the camp. It actually exercises operational control over all activities in the refugee camps and settlements. These indicia of UNHCR’s operational control exercised over the camps entail obligations in international law and one of these is to uphold the rights and freedoms of refugees.

UNHCR recently appears to recognise the centrality of upholding the human rights of refugees to the performance of its functions. In, for example, its 2006 manual, Operational Protection in Refugee Camps and Settlements, a reference guide that ‘seeks to improve implementation of protection’ and ‘strengthening our working relationships with refugee women, men, girls, and boys as active and respected partners, who contribute to and take part in the decisions regarding their protection and future lives,’[6] UNHCR emphasizes ‘a rights-based approach’ as a crucial methodology of realising the protection of refugees. It states that ‘In a rights-based approach, human rights principles guide all programming in all aspects of the programming process, including assessment and analysis, programme design (including setting goals, objectives, and strategies); implementation, monitoring and evaluation.’[7]

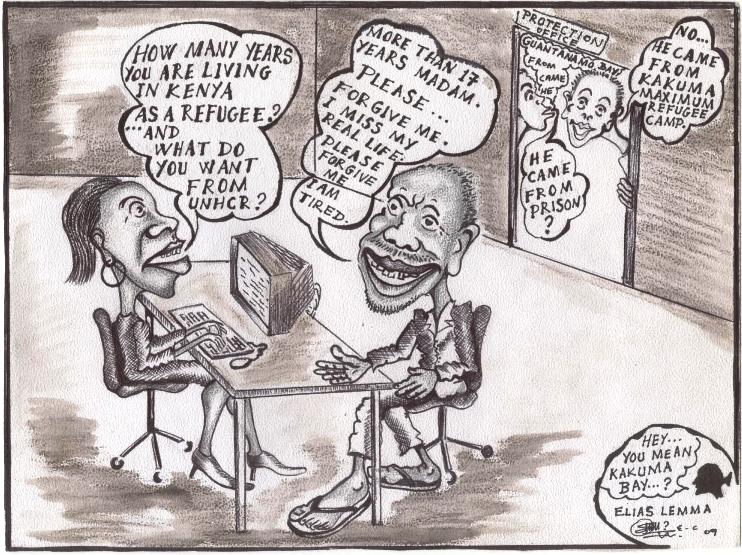

While these are positive developments, as with all other manuals published in the past on refugee protection – on refugee women, children, and unaccompanied minors – for example, practice remains far from the rhetoric. In the refugee camps in Tanzania and Kenya, refugees I interviewed strongly felt that their rights and freedoms were not being fully upheld by UNHCR. Take, for example, participation by refugees in decision-making processes in crucial areas of their lives, such as repatriation, education, and freedom of movement and choice of residence. While acknowledging that they are sometimes invited by UNHCR to come to meetings, these meetings simply serve as place for UNHCR to inform refugees of decisions already taken by UNHCR, in collaboration with the government and implementing partners. Interviewees gave examples: to get refugees to start thinking about repatriations, the closure of secondary schools and small businesses, the reduction of food rations,[8] restrictions on freedom of movement, and delays in obtaining movement permits, arbitrary decisions and actions especially in refugee status determination or assessments of security threats or risks to individuals, and the lack of effective mechanisms for appealing negative decisions. In addition, refugees organising themselves into associations or free press often face hostility far greater from UNHCR staff than sometimes government organs.[9]

In the face of violation of their human rights and freedoms by UNHCR, can refugees seek the intervention of, for example, local courts? The General Counsel of the United Nations, in the current climate of the dominance of positivist legal thinking, within the United Nations, and international lawyers wary of ‘interference’ in the internal affairs of the United Nations, will answer ‘no’ citing the relevant article of the Charter of the United Nations (Art.105 (1)) and the Convention on the Immunities and Privileges of the United Nations on its privileges and immunities. Any attempt by a refugee to do so in a national court following an injury or harm suffered resulting from the acts, action, and omissions of UNHCR will be swiftly followed by a letter from that office to remind the relevant court about the jurisdictional immunity of the United Nations and all its organs, including subsidiary organs such as UNHCR, that operate in the international plane as independent legal persons.

In spite of this, I would still conclude that UNHCR has an obligation to uphold the human rights and freedoms of refugees. It would, borrowing from the International Court of Justice in the Effect of Awards of Compensation made by the United Nations Administrative Tribunal case, ‘hardly be consistent with the expressed aim of the Charter to promote freedom and justice for individuals and with constant preoccupation of the United Nations Organisation to promote this aim’[10] if UNHCR were not to uphold the rights and freedoms of refugees and to be held accountable by refugees where it causes harm or injury to a refugee or a group of refugees.

Zachary A. Lomo

[1] See, Higgins, R., Problems &Processes: International Law and How We Use it,1994.

[2] There are writers, especially those with United Nations work experience, who would dispute this assertion, arguing that UNHCR does not possess separate personality from that of the United Nations. On this aspect, see, e.g., P.C. Szasz, “The Complexification of the United Nations System”, 3 Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations law (1999) 6.

[3] See, Reparation for Injuries Suffered in the services of the United Nations [1949] ICJ Rep. 174

[4] Id., 179

[5] See, e.g., Wilde R., ‘Quis Custodiet Ipsos Custodes?: Why and How UNHCR Governance of “Development” Refugee Camps Should be Subject to International Human Rights Law’, 1 Yale Human Rights & Development L.J (1998)107, 119

[6] See, UNHCR, Operational Protection in Refugee Camps and Settlements: A reference guide of good practices in the protection of refugees and other persons of concern, Geneva, Switzerland 2006

[7] Id. 123

[8] When there is no alternative source of getting food in the camps

[9] From my interaction with UNHCR in Uganda, there are individual staff within UNHCR who not only subscribe to the ideals of incorporating human rights into the work of the organisation, they actually, often at great risk, including risk to their jobs, uphold the rights and freedoms of refugees rather than following operational imperatives in conflict with refugee rights and freedoms.

[10] See, Effect of Awards of Compensation made by the UN Administrative Tribunal [1954] I.C.J Reports, 47, 57.