Volume 1, Issue 1 / December 2008

As of November 2008, Kakuma Refugee Camp has approximately 10,400 pupils in primary schools and 800 pupils in secondary schools. Two thirds of the student population in each case is comprised of boys, while the remaining one-third is girls.

There are currently 14 primary schools and two secondary schools in operation. The educational staff of nearly 250 teachers is comprised of refugee and Kenyans working together under the overall coordination of Lutheran World Federation (LWF) Education Department.

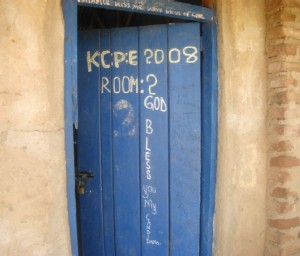

The overall performance of camp schools in national examinations has not been entirely pleasing to all stake holders. Under the primary school syllabus, six examinable subjects are taught: mathematics, science, social studies, religious education, and Kiswahili. In the year 2007, a total of 1,801 students sat for the Kenyan Certificate of Primary Education exam (KCPE) in Kakuma camp schools. Of these, 593 students successfully passed their exams while 1,208 students failed. In other words, only 33% of pupils qualified for the certificate that would allow them to continue on to secondary school.

Where can we look to explain this poor performance? One issue concerns the chronic under-payment of teachers, prompting them to shift to other careers. A high rate of teacher turnover contributes to students’ low performances. Staff recruitment and replacement is disorganized to an extent that it delays the learning process. Even newly recruited teachers do not always stay for long before shifting to greener pastures.

A related issue concerns the collection of food during school days. The World Food Program (WFP) distributes rations twice per month at designated food distribution centers in the camp. For those refugees who have jobs with the health or social services sectors, identity cards are distributed in order to give them priority during long queues at food distribution. Unfortunately, a similar policy does not apply to teachers. Without identification documents, refugee teachers must skip class on food distribution days to persevere with long queues as they await their share of rations.

Food distribution during the school day also affects students’ performance, as pupils are not accorded special treatment during ration collection. Students who live alone or have no other family members to collect rations must incur absences from school in order to collect their food.

As a result of teacher and student absences, food distribution systems in the camp have a negative effect on education standards. One former secondary school teacher shares his experience in attempting to balance food collection and teaching pressures: “I remember a day that I missed food because I didn’t want to miss my class. But there was also a day that I came to collect my rations but couldn’t collect because of a long line and I wasn’t given priority because I had no staff ID. So I had to come back on another day in order to get my food. That means I ended up missing two days of class for my students.”

Language barriers have also exerted a negative impact on education. This is due to the use of English and Kiswahili as the medium of instruction in classrooms. Pupils unfamiliar with either language must struggle to adjust themselves to this challenging learning environment. Bearing in mind that most refugees come from nations that don’t speak either Kiswahili or English, the two language subjects on KCPE exams have proven especially difficult for many learners.

Due to these numerous constraints on the educational environment in Kakuma Refugee Camp, a few refugee parents who can afford to pay school fees have opted to take their children to private schools within the republic of Kenya. As the 2008 academic year comes to an end, there are no hopes for better things to come.