Volume 1, Issue 4-5 / March-April 2009

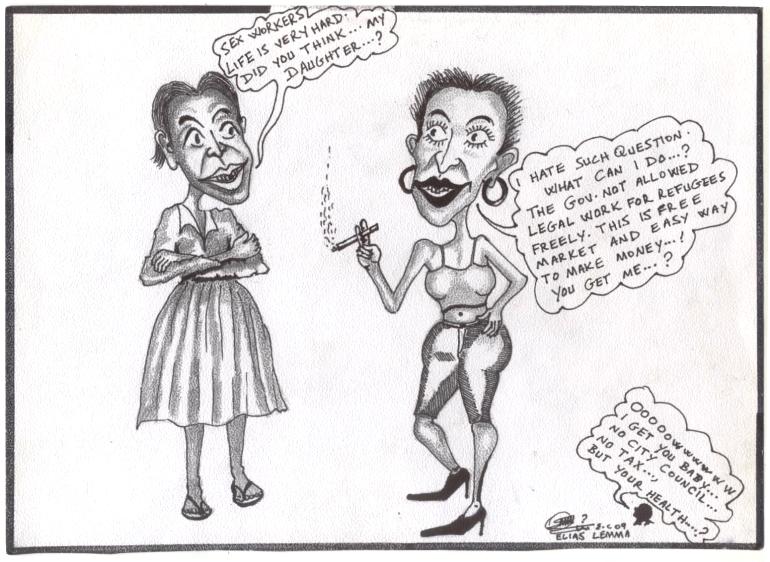

Commercial sex workers in Kakuma Refugee Camp report that they are forced by poverty and dependency to resort to their profession, despite grave risks

The oldest profession on earth is no stranger to Kakuma Refugee Camp. The hostile conditions, powerlessness, and dependency of refugee encampment expose women to especial risk.

The oldest profession on earth is no stranger to Kakuma Refugee Camp. The hostile conditions, powerlessness, and dependency of refugee encampment expose women to especial risk.

“I am a single mother. I stay with my five children, and one was killed. Now that I have no job and nobody can help me with money to buy food for my children, the only alternative is to engage in commercial sex work,” says Mama Clina*, a Rwandese single mother who also runs an illicit brewery.

It is difficult to know how many commercial sex workers are active in the camp. An official from NCCK (National Council of Churches of Kenya) says they do not separate commercial sex workers in their programs due to fear of discrimination, so they are integrated with other groups and cannot be easily traced.

One commercial sex worker told KANERE that she knows they are many but cannot estimate the actual number.

A matter of survival

Commercial sex workers say that poverty forces them to their profession.

“I did not choose to be a commercial sex worker. If I can get an income to satisfy my children and my needs, why should I continue to bear the branding from my women colleagues in the community that I snatch their husbands?” asks a Ugandan commercial sex worker.

“Yet I force nobody to come and see me,” she adds.

One woman paints the picture plainly. “I have to sell what I have. It is my body because other people sell their good from their shops.”

Most commercial sex workers in Kakuma are single mothers who lost their husbands during war and conflict in their own countries. They say that it is not safe for them to return to their home countries, but life in the camp is also challenging. Although refugees receive food rations every fortnight, commercial sex workers report that it is not sufficient.

“Food and firewood that cannot last these two weeks! Where is meat, fish, green vegetables, and fruits? Other refugees working with NGOs can buy these. Our bodies too need these foods that are not distributed by WFP, and our children are suffering,” Mama Clina says.

According to Mama Clina, clients consist of NGO workers, refugees, and locals. “When customers come to take our beverages, chang’aa, busaa, or ingenzi [local illicit brews], they also request us to have sex with them. The client pays me as he appears. When he is an NGO staff and is smart, he pays me 300 to 500 Ksh, but the rest I charge 100 to 200 Ksh,” Mama Clina says.

She reports that most sex workers see about two clients per day, on average, and earn at least 200 Ksh towards their daily bread.

Other women in the camp community are not happy with sex workers’ behavior. Some do not understand the women’s motives. “Some of the commercial sex workers are sick. Even if you give them millions of money, they will still want to sleep with men. However, I want to say that they are poorer than us,” one Rwandan woman told KANERE.

NCCK seeks to offers alternatives to sex work

NCCK, an NGO working with reproductive health in the camp, started income-generating activities in 2005 to alleviate women’s vulnerability in the camp.

“We empower them economically through offering catering services, whereby they use some capital and we pay back together with interest.† Apart from catering services we also offer them alternative livelihoods through hairdressing, small foods kiosks, peanut butter production, poetry, tailoring, and selling soft drinks,” says the NCCK Project Coordinator, Mr. Rafael.

The program started with eight women and has since expanded to include 25 women’s empowerment groups, partly comprised of commercial sex workers. Each group is comprised of either five or ten members.

Speaking on the impact of the project to these women, Mr. Rafael says, “We first do reproductive health advocacy to help have safe motherhood and prevention of HIV, safer sex through condom use and change of livelihood. Secondly, the program protects them from violence, arrest by law enforcement officers, risk of acquiring HIV/Aids and STIs, and SGBV [sexual and gender based violence].”

Alternative livelihood programs are meant to assist behavior change among vulnerable women, including commercial sex workers, women living with HIV, illicit brewers, and single mothers with large families.

One NCCK staff who sought anonymity told KANERE that some commercial sex workers refuse to abandon their behaviors during the pre-selection interviews. “They tell us that it is their right to have sex, and they question who will fulfill their sexual needs when why stop. However, they are few. In this case, we offer them health education on safer sex and prevention of STIs and HIV.”

A “grave matter”

But many women enrolled in the program are concerned with the duration of assistance. When the assistance they receive from NCCK runs short, they go back to selling sex.

One Congolese women describes her experience this way: “We are five mothers. In the beginning we were given two bags of rice and beans, per two mothers, that we had to use during our turn of catering services in 2007. We served in that workshop and got around 3000 Ksh of interest. The workshop is held once per year or year-and-a-half. Can these 3000 Ksh sustain a family life of four people for the whole year?”

“It is difficult to leave commercial sex work in this situation,” she continues. “Even the grant they give us to start will have been consumed all at the end of the year.”

Women are aware of the health risks that attend their work. Several commercial sex workers who spoke to KANERE referred to their profession as a “grave matter,” referring to the risk of serious health consequences. They know the long-term dangers of their work, but say they have no other way to survive in the refugee camp.

Two women told KANERE that they are HIV positive. Sometimes their clients refuse to use condoms, while others assent. They say they have no choice in the matter, as condom use depends on their clients’ preference.

The women report that they do not attend regular medical checkups. They only seek medical attention when a disease becomes significant enough to interfere with their work.

Seeking empowerment

Women engaged in commercial sex work told KANERE that their message is to be empowered completely so that once they accept change, there will be no chance to turn back. They want to enjoy life like any other member of their community.

Community members, leaders, and NGOs should work together with the Government and UNHCR to provide vulnerable women with more employment and income-generating opportunities to support their self-reliance and avoid the risks that await them.

*Not their real names.

† Not to be confused with the women’s catering groups of LWF which were dissolved in January 2009. (See: “Women’s Empowerment, But Only for a Moment.”)