Volume 1, Issue 3 / February 2009

By Ekuru Aukot

Dr. Ekuru Aukot of Kituo Cha Sheria writes on the right of refugees to exercise a free press in Kakuma Refugee Camp, and their obligation to uphold the ethics of professional journalism

Introduction: the camp environment

Free press or the right to free expression is a human right duly recognized by international human rights law as well as under Kenya’s domestic law. In the context of Kenya, refugees reside in the urban and rural locations of Nairobi, Mombasa, Nakuru, and Kakuma and Dadaab refugee camps respectively. A fundamental question is whether while in the camp environment, refugees enjoy fully all the rights under the international and regional conventions, that is, the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status Refugees and the 1969 OAU Convention on the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa.

This editorial focuses on the Kenyan legal context and attempts to answer the question whether stakeholders, including the government of Kenya and humanitarian agency workers generally, believe in the rights of immigrants. More specifically, do all the people who work with and amongst refugees and asylum seekers believe in their rights, and particularly the right to a free press? How do refugees seek to exercise this right in the camp environment? The camp, it must be recalled, restricts the enjoyment of the right to freedom of movement, amongst other rights.

The human rights discourse

The right to a free press for refugees and asylum seekers is about the human rights discourse. The pursuit of this right draws inspiration from a number of treaties and international norms agreed to by member states of the United Nations. One would recall the provisions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) followed later by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) as well as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). All these treaties, inter alia, have been ratified by Kenya.

It is instructive to note that despite the plethora of international treaties on human rights, enjoyment of human rights generally, and specifically that of a free press, is not easy. Rights are not given and for one or a group to enjoy any rights, they must seek them and must get them. A free press particularly is often interpreted differently depending on what interests are at stake, and on what the free press is exposing or about to expose. States may restrict this right in the excuse of national security. Other authorities such as humanitarian agencies may restrict its enjoyment owing to the fact that to allow refugees, for example, to exercise this right fully may cause embarrassment and would open a series of criticism.

Free press is, in fact, the right to freedom of expression which has legal basis in a number of legal texts. The fact that refugees are protected in Kenya and asylum seekers are afforded due process to claim refugee protection speaks of a trail of partners who believe in the rights of refugees and asylum seekers. At the top of that list is obviously the government of Kenya that allowed refugees to reside in Kenya and then allowed the operation of United Nation agencies such as the UNHCR and the WFP to operate in the camp. This clearly indicates the acceptance of refugees and asylum seekers as rights holders. The converse is that the government and UNHCR are the duty bearers to ensure that rights holders enjoy those rights. Arguably, therefore, the government, the judiciary, NGOs, and refugees and asylum seekers believe in their rights as a special group of immigrants in Kenya. The belief in those rights does not exclude the right to a free press.

I must, however, single out the work of the UNHCR in this regard. The UNHCR conducts RSD or eligibility, a function that is the duty of the receiving state. It is arguable that UNHCR bails out the Kenyan state and by exercising the functions of the state, UNHCR may end up compromising itself. It is for this reason that when refugees would exercise the right to free press and write about the work of UNHCR, it may be interpreted in a negative light. This may be the result of reversed roles in the camp context-while exercising this right, refugees would not avoid criticizing the work of UNHCR and its implementing partners in the camp.

The fundamental question that arises is whether refugees, while enjoying this right, should exercise caution in what they write. Should they be governed by professional ethics? Should refugee narratives be balanced, especially if they find their way into a publication such as the Kakuma News Reflector, which is web-based? I shall endeavour below to lay down the law and ask 1) whether in the exercise of this right, refugees are within the law; and 2) whether anyone attempting to curtail that right is breaching the law.

Exercising the right to free press within the context of Kakuma News Reflector

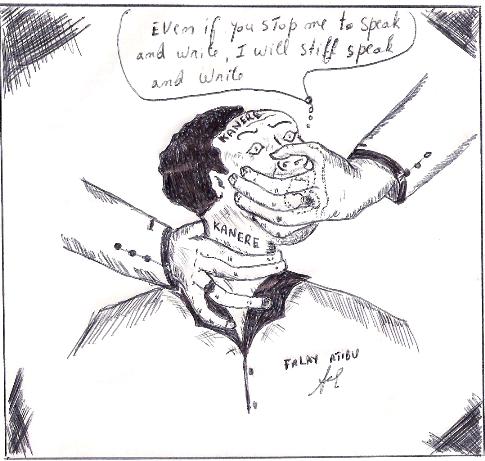

The Kakuma News Reflector (KANERE) brings together local and refugee journalists who desire to exercise the right to a free press. This endeavor has brought many questions to the fore, and key among them is whether refugees and indeed anyone within the jurisdiction of Kenya has the right to free press. This right is intrinsically connected to the right to freedom of expression. It must, however, be noted that the right to free press does not necessarily give journalists absolute freedom to publish whatever they feel, especially if it is inaccurate or injurious to persons they write about. Refugees are no exception to this rule-a free press also calls for the ethics of journalism as a profession. However, to try to curtail this right without any reason would be to violate not only international human rights treaties ratified by Kenya, but would also be violating the Constitution of Kenya, which is the grund norm. It would also violate the Refugees Act, 2006 which is more specific on the rights of refugees.

A background check indicates that KANERE is experiencing registration problems simply because their intention to enjoy the right to free press is not being given approval by stakeholders working with and amongst refugees. This includes the government of Kenya, which is frustrating the registration of KANERE as a community-based organization to work in the camp environment. It is in that context that this editorial is being written.

In fact, the legal framework in Kenya supports the claim by refugees to a free press. Following are some of the relevant provisions under the Kenyan Constitution and the Refugees Act, 2006.

The Constitution of Kenya. The Constitution of Kenya at Chapter 5 guarantees the “rights and fundamental freedoms of the individual.” If one were to read section 70 thereof together with sections 71-83, this would also refer to refugees. Those rights and fundamental freedoms fully accrue to refugees now resident in Kenya’s refugee camps. In fact, section 70 reads like an abridged definition of the refugee under the conventions, as it makes reference to some of the so-called five golden grounds that give a well-founded fear of persecution. Following Article I of the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, the Kenya Constitution makes reference to race, religion and or discrimination generally.

Included under the rights and fundamental freedoms of the individual is the right to freedom of assembly, association and expression. Should any of these rights and freedoms be threatened, section 84 of the Constitution outlines enforcement provisions. Anyone within the jurisdiction of Kenya can petition the constitutional court that their rights have been infringed, continue to be violated, or that they are likely to be violated. So in the light of the concerns involved in KANERE’s case, one would clearly challenge anyone frustrating the enjoyment of those rights on the strength of constitutional provisions.

The Refugees Act, 2006. The Refugees Act incorporates or domesticates all the human rights treaties to which Kenya is a signatory to or has ratified in Section 16. This means that refugees’ rights of assembly, association and expression as provided in any other human rights treaty are now protected and are therefore part of Kenyan law. On that basis alone, the desire of the journalists to exercise freedom of expression under the auspices of KANERE cannot and should not be seen as violation, as it is simply an avenue via which refugees express their freedoms and enjoy their rights.

In fact, should members of KANERE feel threatened in the exercise of a free press, they have recourse in the Kenyan constitution for they can petition the Constitutional Court under Section 84, the enforcement section. They could also rely on the particular provisions of section 16 of the Refugees Act, which they can ask the constitutional court to interpret in as far as the right to exercise a free press is concerned.

Furthermore, the Freedom of Information Law has recently been enacted by the Kenyan Parliament as a development towards the agitation for the enjoyment of rights by individuals and institutions, and I believe this is where KANERE falls in.

Conclusion

I am therefore not satisfied that should refugees choose to exercise the right to a free press through KANERE or any other medium, anyone would be justified in inhibiting this right. No one should see KANERE as threatening, for example, the security of Kenya, for that is often what typical bureaucrats would argue. There are more worrying and pressing things in Kenya at the moment than to worry about the freedom of individuals to speak out, whether exercised by refugees or Kenyans.

Even if we were to set aside the Constitution of Kenya and specific law on refugees, there is still the principle of residuary rights which even prisoners enjoy, or any one whose freedom is restricted. Refugees are no exception to this. In fact, for the avoidance of doubt, refugees are not anywhere close to being treated like prisoners unless that is what someone within those working with refugees is intimating.

I would argue that refugees have only found themselves in the camp because of government policy which is being implemented by those working with refugees, and not because the law requires them to be there. Even if we were to still keep refugees in the camp, or continue to “warehouse” refugees, this does not take away refugees’ rights and in particular that of a free press. It must also be remembered that refugees bring with them all manner of trades that were interrupted in their countries of origin, and that includes those who may have been exercising journalism as a profession and those whose flight denied the opportunity to exercise journalism.

Lastly, I am often guided by the wise words of Philip Halsman that “it is not only a bundle of belongings a refugee brings to his new Country. Einstein was a refugee.” Refugees in Kenya, too, bring all their trades and are eager to exercise them.

Author’s Background: Ekuru Aukot holds a PhD in International Refugee Law from the University of Warwick Law School, UK; he lectures at post graduate level, the Law on Refugees & IDPs at the School of law, University of Nairobi; an Advocate of the High Court of Kenya; a co-founder/Director of the Northern Frontier Districts Centre for Human Rights & Research (NFD-CHR); the Executive Director of Kituo Cha Sheria (The Centre for Legal Empowerment); a member of the Council of the Law Society of Kenya. This write up benefits immensely from the work of the Urban Refugee Intervention Programme (URIP) Centre currently established by Kituo Cha Sheria at Eastleigh as a physical facility where refugees and asylum seekers would simply walk in for free legal advice/representation on any issue affecting the enjoyment of their human rights in Kenya. To that extent I thank my colleagues at the URIP centre, Saniyo (a very able and an Oromo refugee who in our view at Kituo is the first advocate for refugee rights in Easleigh), Laban, Moses, Okiring (a lawyer and an enthusiast of positive political change in Uganda), and Zahra for their committment at the URIP Centre.

Appended: Excerpts from the Law

The Constitution of Kenya

Chapter 5, Section 70: “Whereas every person in Kenya is entitled to the fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual, that is to say, the right, whatever his race, tribe, place of origin or residence or other local connection, political opinions, color, creed or sex, but subject to respect for the rights and freedoms of others and for the public interest, to each and all the following, namely-

(a) Life, liberty, security of the person and the protection of the law;

(b) Freedom of conscience, of expression, and of assembly and association…”

Chapter 5, Section 79: (1) “Except with his own consent, no person shall be hindered in the enjoyment of his freedom of expression, that is to say, freedom to hold opinions without interference, freedom to receive ideas and information without interference, freedom to communicate ideas and information without interference (whether the communication be to the public generally or to any person or class of persons) and freedom from interference with his correspondence.

(2) Nothing contained in or done under the authority of any law shall be held to be inconsistent with or in contravention of this section to the extent that the law in question makes provision-

(a) that is it reasonably required in the interests of defence, public safety, public order, public morality or public health-

(b) that it is reasonably required for the purpose of protection the reputations, rights and freedoms of other persons or the private lives of persons concerned in legal proceedings, preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, maintaining the authority and independence of the courts or regulating the technical administration or the technical operation of telephony, telegraphy, posts, wireless broadcasting or television; or

(c) that imposes restrictions upon public or upon persons in the service of a local government authority…and the thing done under the authority thereof is shown not to be reasonably justifiable in a democratic society.”

Chapter 5, Section 80: (1) “Except with his own consent, no person shall be hindered in the enjoyment of his freedom of assembly and association, that is to say, his right to assemble freely and associate with other persons and in particular to form or belong to trade unions or other associations for the protection of his interests.”

Refugees Act 2006

Section 16. (1) “Subject to this Act, every recognized refugee and every member of his family in Kenya-

(a) shall be entitled to the rights and be subject to the obligations contained in the international conventions to which Kenya is party;

(b) shall be subject to all laws in force in Kenya.”