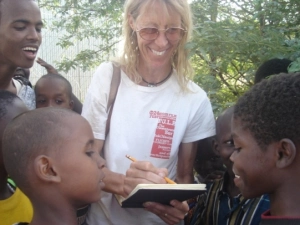

Sally Lincoln, an American artist, shared her vision and knowledge with refugees in Kakuma Camp during her four-week mission to paint refugee portraits

An American artist, Sally Lincoln, visited Kakuma Refugee Camp to paint refugee portraits after discovering the Kakuma News Reflector weblog. Ms. Lincoln shared her work and life experiences with refugees through her vision of art as a way of expressing human reality.

“Why is an American artist applying for an extension in a refugee camp?”

Ms. Lincoln arrived in Kakuma Camp on 29th January 2009 after waiting eight days in Nairobi for a permit to enter Kakuma Refugee Camp from the Department of Refugee Affairs in Nairobi.

She says that KANERE brought her to Kakuma Refugee Camp. “I was trying for a long time to find a refugee newsletter. Fortunately I found KANERE online while I was in the U.S. I wrote to the editor who replied to me quickly!” says Ms. Lincoln. “I’m excited that there are refugees in the camp writing about their life and the surroundings. I look forward to reading future issues.”

Upon arrival to Kakuma, Ms. Lincoln made a few observations. “Kakuma is not an easy place to live. Visitors to the refugee camp sometimes bail out before their scheduled departure dates. It’s hot, grit-laden, and winds are utter torment to a contact-lens wearer.”

The camp is not widely regarded as a pleasant destination. “Most, probably all, of the camp’s 50,000-plus inhabitants want nothing more than to leave,” she says. “Even the staff of NGOs are given one week out of every eight to go somewhere else for relief.”

Amid these difficult circumstances, she notes the irony of her situation: “So why is this American artist applying for an extension to her visitor’s permit?”

Ms. Lincoln’s visitor’s permit to Kakuma Camp was initially scheduled for two weeks. After that time passed, Ms. Lincoln extended her permit for another week. Although she had planned to depart for a trip to Ethiopia after her third week in Kakuma, she found that she was unable to leave.

“I couldn’t leave! I couldn’t leave my students. The artistic opportunities here are like nowhere else in the world,” she says. As this issue goes to print, Ms. Lincoln remains in Kakuma, sharing art, conversation, and coffee with her pupils, friends, and fellow artists.

An artistic mission

Ms. Lincoln’s mission is to paint portraits of people who are undergoing changes of identity. She believes that refugees are one such group: “They are changing in themselves-they have left home, and it’s very difficult to keep a sense of your own identity.”

In the midst of change, portraits serve as a testimony to an individual’s presence and experience. Of the portraits, Ms. Lincoln says, “This is something different. Something important about me! I was here!”

She says she chose to focus on refugees because she likes painting people who would not otherwise have a chance to be painted by a professional artist. “I felt this was for refugees, particularly for the long-term refugees, to get more publicity. I feel more that this is a deeply important part of human life. I know there is a lot of talent and I know there’s lots of demand,” says Ms. Lincoln.

She believes art is a defining element of human life and culture. “Art enhances the quality of human life,” she explains. “It has been a part of life for as long as we have been human. No other being has art. Goats, donkeys, sheep-no art.” She points out that art is also enduring-the first indications of human culture come from cave paintings and sculptures preserved for millennia.

Ms. Lincoln’s art serves in community development and fosters a healing power for the people. “It normally gives people their presence in the world, and I think people feel good about themselves for being on the website,” she says, referring to her online art gallery at www.sallylincoln.com.

Ms. Lincoln does not receive payment for her portraits and her visit to Kakuma was self-funded. “There is no direct benefit in any financial sense, but I give people experiences so they may feel good and enjoy. Sometimes they burst out saying that they’re so interested in my art,” she says.

“Refugees have an abundance of time”

Each morning, Ms. Lincoln devoted herself to painting portraits of refugees who volunteered as subjects. After taking a photograph of the completed portrait, Ms. Lincoln gives the painting back to the person who was painted.

She paints people live, just as they appear. “It takes a lot of time to paint people-usually about two hours, or sometimes more,” she says. “No one thinks of refugees as being wealthy in any way, yet those in refugee camps have an abundance of one commodity in short supply almost everywhere else-refugees have time.”

Each afternoon, she held drawing lessons open to all. A group gathered every day at 3 p.m. at Turkana Cafeteria to draw together for two hours. “There are no entrance requirements,” Ms. Lincoln says. “Any age may attend. Students may draw whatever they want. The only rule is this-you may not be discouraged. I draw along with everyone else.”

Through her lessons, Ms. Lincoln hopes to dispel the myth that artistic skill is a rare or impossible gift. “As an artist, I’m always trying to convince people that drawing is not about ‘talent.’ If there are people who are born knowing how to draw, I am definitely not one of them. I spend about ten hours each week working to improve my skills through practice, and I am rewarded for this effort by achieving a proficiency I couldn’t have imagined even a year ago.”

Her teaching philosophy is less about teaching, and more about doing. “People often ask me if I can teach them to draw. I tell them that they don’t need me; they can teach themselves. All they need to do is draw for two hours a day with a group of other people and after five years they will be better than I am.”

“Very simple,” she claims. “No one ever believes me.”

Her time in Kakuma provided direct insights into her philosophy of art. “I have had a good opportunity to put this theory to the test,” she reports. “For the students who have come every day, progress is already quite evident. I think most of the students would tell you also that the time they spend drawing is time they enjoy.”

Ms. Lincoln says she has enjoyed wonderful interactions with communities every day. “I eat meals in the Ethiopian town. I meet people. People see me drawing and they ask me to draw them and everyone is so kind to me,” she says.

The refugees are terrific and capable, she adds. “They can help in anything in their capacity. For example, if I wanted kerosene or paraffin, someone could find it for me, wherever it is!”

“I will remember who painted me”

Refugees who participated in Ms. Lincoln’s art classes were profoundly impacted by the opportunity.

David, aged 15, is a Sudanese refugee from the Nuer Community. He explained that he acquired good experience in the production of art and drawings. “I can draw and learn more how to draw! I will remember who painted me. I will hang the portrait on the walls of my house,” says David.

Ismael is a 17-year old refugee from the Congolese community who joined Ms. Lincoln as a student and portrait subject. He reports that painting the portrait took “a lot of time.” But after it was done, “Ms. Lincoln gave me the portrait and I felt so good. I’ve taken the portrait home. I feel great appreciation to see my picture and I never paid any money for this.”

Ismael enjoyed the opportunity to develop his artistic skills through Ms. Lincoln’s lessons. “I got good experience. I like my image, and I can now draw cartoons of trees and also the people,” he says.

Many students attended Ms. Lincoln’s dynamic art lessons over the course of her time in Kakuma, with diverse student groups ranging from young children to adults with professional artistic experience. Students could be seen sketching rapidly changing scenes in the Somali market, or honing their approach at Ethiopian coffee houses.

David reports that he would like to become a professional artist like Ms. Lincoln, while Ismael aims to become a professional cartoonist and writer one day. Both David and Ismael say that they will take their portraits everywhere they go in the future.

“The next generation of great artists”

Ms. Lincoln says she was shocked to learn that refugees are staying in the camp for such a long time. She says the encampment of refugees should be better known to the rest of the world, especially through live coverage of their situation.

She notes that the consequences of such long-term encampment are not positive. Humanitarian organizations may feed, educate, and take care of refugees, but without a voice, she says, nothing can be known about the claims of refugees.

“For the world of art, Kakuma is an enormous hidden opportunity,” she says. “I believe that the world’s refugee camps could produce the next generation of great artists. It seems well worth sticking around for a while to see if I can help that happen. If you are in Kakuma, stop by sometime to see how it’s going.”